June 10, 2024

Do It With Kindness; or, Why a Skateboard Can (Sometimes) Be Faster Than a Ferrari

The advice I left for my team on my last day as an engineer at HashiCorp

This post was originally shared with my team at HashiCorp on my last day. It has been edited to account for a broader audience.

I spent a lot of time at HashiCorp thinking about how I could help others level up their engineering skills. With that in mind, I wanted to make one final attempt to share some of the things that I think engineers can do to distinguish themselves apart from the rest. This, of course, isn't an exhaustive list, as any attempt to do so could probably fill several libraries, but I do think it captures some of the qualities that I've seen in the engineers I look up to and admire.

Read the error message/code/documentation

One of the really awesome things about software engineering is that if you don't know how something works, you can simply go read the code (well, when you have access to the code that is!). Get really, really good at that. In high school, my computer science teacher frequently told us that "computers don't do anything you haven't told them to do", which was a really nice way of telling us to stop complaining and just read the code that we had written. In large codebases it's unreasonable to expect engineers to understand off the top of their heads how everything works, so being able to open an unfamiliar piece of code and read it top-to-bottom and understand what it's doing is a skill you'll benefit from.

Similarly, get good at reading error messages and documentation. I can't count the number of times when an error message contained the specific piece of knowledge that I needed to go solve the issue. Even when an error message is terrible, it often comes with a stack trace, so you can see all the lines at play that resulted in a specific error. Jump into the code and walk backwards, and you'll likely figure out what the issue was, even if the error message was unhelpful.

Documentation is another thing that you should be good at reading. Frameworks like Next.js have tons of documentation detailing their features and functionality. If you haven't read through them at least once I highly suggest doing so, if only to drop breadcrumbs of knowledge that you can pick up when you run into issues.

Get good at searching

Learning how to search for things, whether it be on Google, Slack, GitHub, Datadog, or some other service, is such a superpower. In just a few seconds you can search across an unfathomably large amount of information, and being able to do so effectively can really boost your productivity. I find this most useful when searching after encountering an unfamiliar error message. One thing I really find useful is searching for the portion of the error message that is unlikely to appear in anything other than the error message itself but is also applicable enough that it will match against all instances of the error. In these situations, performing exact searches (usually by using quotations) is also a great strategy. Most search features have additional filters to narrow down the results, so make sure you're learning about and using those. For example, I frequently used the org:, language:, and path: filters in GitHub Search.

Getting good at search is often just a matter of being able to intuit the pieces that are likely contributing to the error. As an example, a documentation author at HashiCorp was having issues with Docker on their MacBook where one of my team's Node applications would simply output "Segmentation fault" and exit. However, another user running the exact same branch on their MacBook did not encounter the same error. The first user was using an Intel Mac, whereas the second user was using Apple Silicon. With that information I Googled "docker node segmentation fault intel mac" and the first result was this issue from over a year ago, which had some helpful configuration changes that we were able to make to get the Intel user back up and running.

Being good at search isn't just for error messages though. In organizations that use tools like Slack and Google Workspace, you can dig up some incredible things by using search. I frequently used Slack to look up previous conversations to get background on why certain decisions were made, especially when the people who made them were no longer at HashiCorp. Tools like Google Cloud Search (which allows you to search for text in anything hosted in Gmail or Google Drive) were similarly useful in finding old documents and slide decks, something I found myself referencing a lot, especially when it came to decisions made outside my team.

Make minimal reproductions

When it comes to debugging, being able to make a minimal reproduction of the issue is basically the holy grail. Many open source projects won't even look at a bug report without one. The reason they're so good is that they boil the issue down to the pieces that are necessary to make it happen, and nothing else. This allows you to narrow your focus to just the pieces at play, and easily confirm if your changes resolve the issue. During my time at HashiCorp, I made dozens of minimal reproductions that ultimately resulted in pinpointing the source of an issue. These reproductions also helped the Next.js and Vercel teams fix issues on their end, ultimately benefiting all of their customers. Whether you start from scratch or start pulling pieces out one by one, being able to end up with the problem distilled to its most minimal form is a powerful skill to have.

To give an example, about a year ago one of our team members ran into an issue with dynamic routes after updating Next.js where pages would render with data from the incorrect page, but only when our application was deployed to Vercel. They opened a support case and worked with Vercel to try and track the issue down, but after a month of back and forth, were unable to narrow down the issue enough to come to a resolution. When it began to block our ability to update to Next.js v14, I sat down with my coworker's notes and took a few hours to build a reproduction that was just a handful of files and reliably demonstrated the issue. When I shared that with Vercel, they were able to deploy a fix in just 10 days.

Try to figure it out yourself first

When you run into a problem, make a decent attempt at figuring it out on your own before you call in reinforcements. Don't spend too much time, especially if you're truly stuck, but you should at least try to solve the problem yourself. This allows you to build up experience with unfamiliar systems, and helps you develop your own understanding. Pairing with other people is a productivity boost, but it can also easily become a crutch holding you back from developing your own skills, especially if your pairing partner isn't experienced enough to help guide you to the solution, and instead simply tells you what the answer is.

Align how long it takes to make a decision with how long it takes to unmake it

Allen Pike has a great article titled "Do Something, So We Can Change It" which I highly recommend reading. I often like to think about technical decisions in terms of how long it takes to undo a change. If it takes half an hour, there's no reason to spend two weeks trying to come up with a perfect solution. If it will take six months to undo, maybe make sure you're really confident that your approach is the correct one. Don't spend tons of time worrying over small, easily reversible decisions. Save that time for the big, complicated, thorny problems.

It's okay to be wrong, but don't become known for it

The best engineers I've ever worked with were the ones who weren't ashamed to admit they didn't know something. Instead of making something up or guessing, they were honest that they had no idea. As we become more experienced, there's this desire to maintain our prestige in the eyes of others, which often leads us to feeling discomfort when admitting we don't know something. That's totally okay! I can't recall a single instance where an engineer admitted they didn't know something and I thought less of them. However, there have been times in which an engineer confidently answered a question with incorrect information, without any qualification that their understanding wasn't complete. This is always an awkward, uncomfortable situation because correcting misinformation in a kind way takes a large amount of skill. It's always easier to just admit you don't know something, because you don't want to build a reputation for giving unreliable information.

Be (a little) lazy

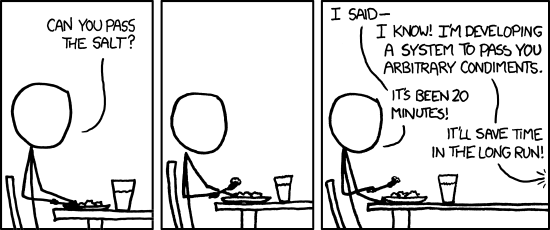

Look, I understand the allure of building wonderful, beautiful, complicated systems, but sometimes the best thing is the laziest approach. Instead of trying to build something that covers every possible edge case, build the thing that covers the majority of the non-edge cases, and iterate from there. At HashiCorp, we talked a lot about "building a skateboard", which originates from a talk by Henrik Kniberg, instead of jumping straight to building a car. We also started using the term "bus ticket" for something that currently exists and can be used without building something new. This way of thinking allows you to avoid spending a lot of time doing something that isn't quite the right thing.

Knowing when to go with the easy approach and when to spend the time building the "right" approach is a skill that only comes with time and experience, but you can start by asking yourself "What is the easiest way to solve this problem?" Start from that solution, and expand outwards, instead of jumping straight to the solution to solve all instances of an entire class of problems.

So, what does the lazy solution look like? Sometimes it's just copying and pasting code instead of trying to fit two use cases into the same API. Sometimes it's copying in a small dependency and modifying it slightly instead of making a pull request and waiting for a change to be merged. Sometimes it's accepting that you're only going to be able to handle a specific set of circumstances automatically and being okay with handling the other cases manually.

All this being said, don't take this as advice to be bad at your job, or to take shortcuts that result in worse outcomes. Being lazy has nothing to do with not doing the work that needs to be done. It just means avoiding work that doesn't really need to be done.

Be okay saying "No"

You don't need to immediately say yes to every idea presented to you. Your best work will be highly opinionated. Believe it or not, the customer isn't always right. (An alternative version I've heard is "the customer is always right in matters of taste", which feels more like something I could get behind.) Often their ideas don't account for the full context at play, and likely aren't the best possible solution to the underlying problem. If someone approaches you with a specific solution, take the time to dig into what the actual problem is, and then try to solve that instead of simply saying "Yes" to whatever they've proposed. This is hard sometimes, and impossible in others, but is necessary if you want to have good results.

Do everything with kindness

Finally, in everything you do, do it with kindness. I can think of no worse outcome than becoming known as the person who doesn't. At the end of the day, our jobs are not so important that it's worth being unkind to someone else. Always assume that others are acting with positive intent, and ensure that your words and actions build others up instead of tearing them down. Focus on critiquing ideas, not people, and make sure your critique is constructive and actionable; there's no value in simply saying an idea is "bad". When others present ideas, even if you disagree, offer to work together to build towards something that you can agree with. Do this with eagerness and excitement. Working with others is a joy if you let it be, and even more so if you're a joy to work with yourself.